Attempting first to take hold of the exhibition space…to go against these overly familiar, well-worn places, to grasp the limits, the walls, the height of the ceiling, the openings, the passages, the floor ; to favor the sparse, to embrace emptiness for once, and finally to twist space as if it were pivoting around the objects.

To be able to say, “the right viewing angle is here” and to refuse the transformation of pieces, objects, and forms into sculpture. Instead, to allow them to stand as a landscape to be contemplated, inviting neither movement around them nor touch, nor the physical crossing of their space.

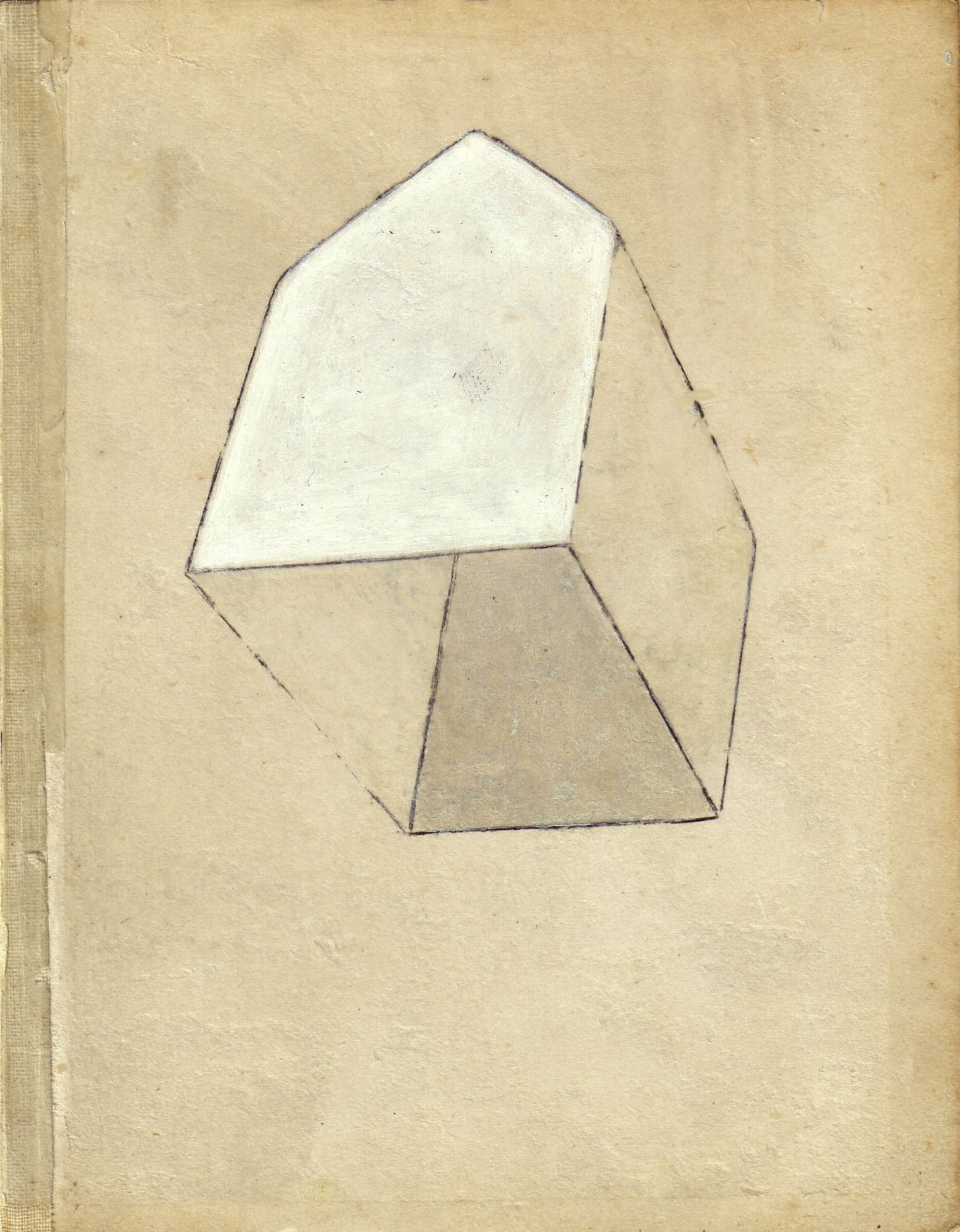

Plan—construction—arrangement; this becomes essential. First, the drawing begins, initiating the progression of an idea. A motif, repeated on paper with an unaffected stroke, the obsessive search for a paper slightly aged, imbued with history—this forms the foundation of each series.

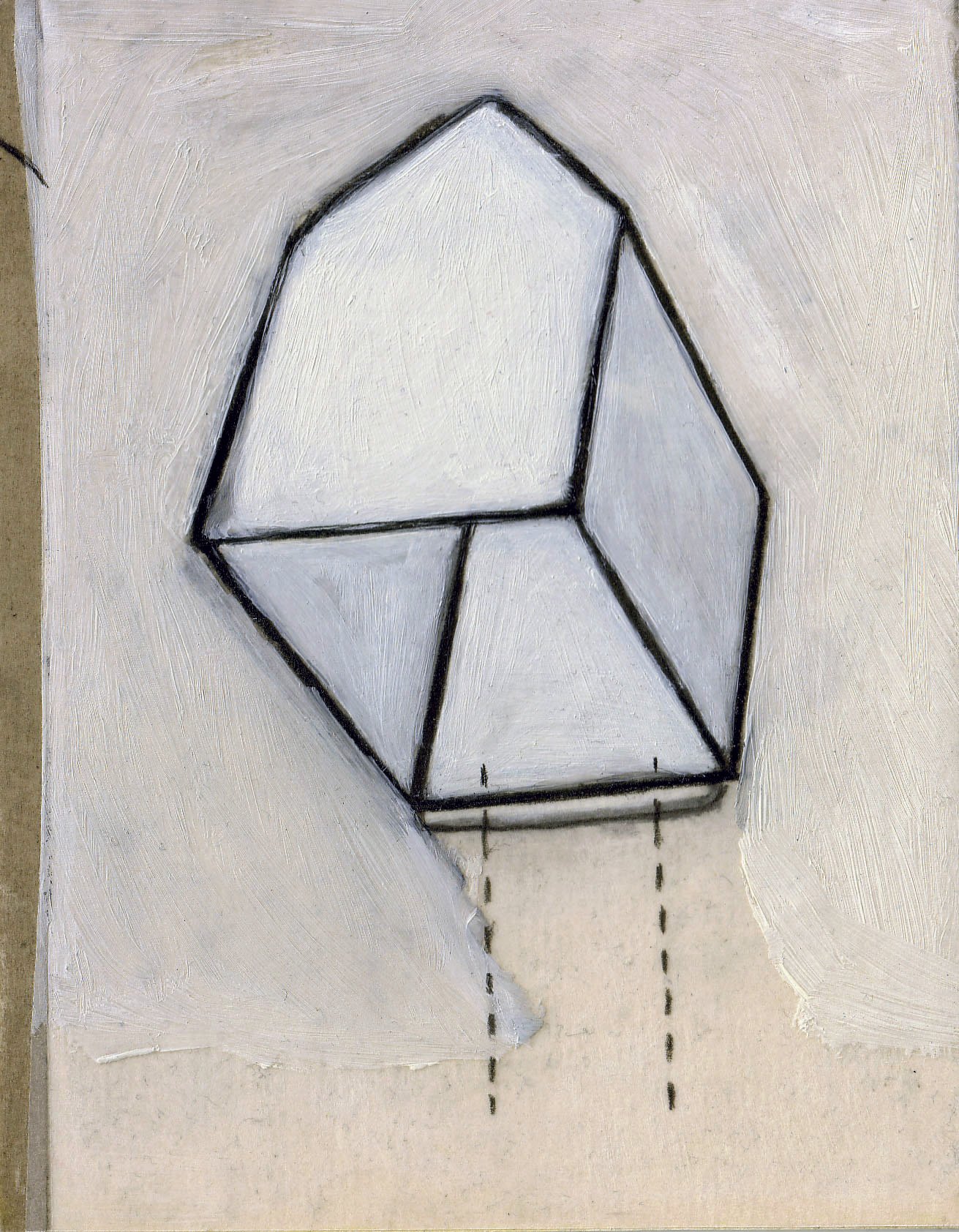

A hollow volume, perhaps a house, more certainly a box, propelled by an imperceptible force—an ascent viewed from below in perspective, the lessons of the Renaissance need not be forgotten. Here, the repetition of the motif eventually exhausts the figure, leaving only a sign.

To eliminate, to refine away all detail, to remove yet more—the space must become an immediate field of tension. One thinks of « Suprematism: Blue Triangle, Black Rectangle » by K. Malevich (1915), the reduction to the elemental—form, color—that is what liberates all energy.

Construction finds its passage to become the formal equivalent of the idea. It does not merely materialize it; it draws from the drawing its energy. For the drawings are not mere accompaniments to the installations placed by the artist within the space, but rather matrices containing the full potential of the work.

Even when built in volume, even when installed within the exhibition’s walking space, the three-dimensional structures return to a graphic simplicity: black “boxes,” lines of metallic bases, visible copper wires, electrical wires, hair—between model and architecture.

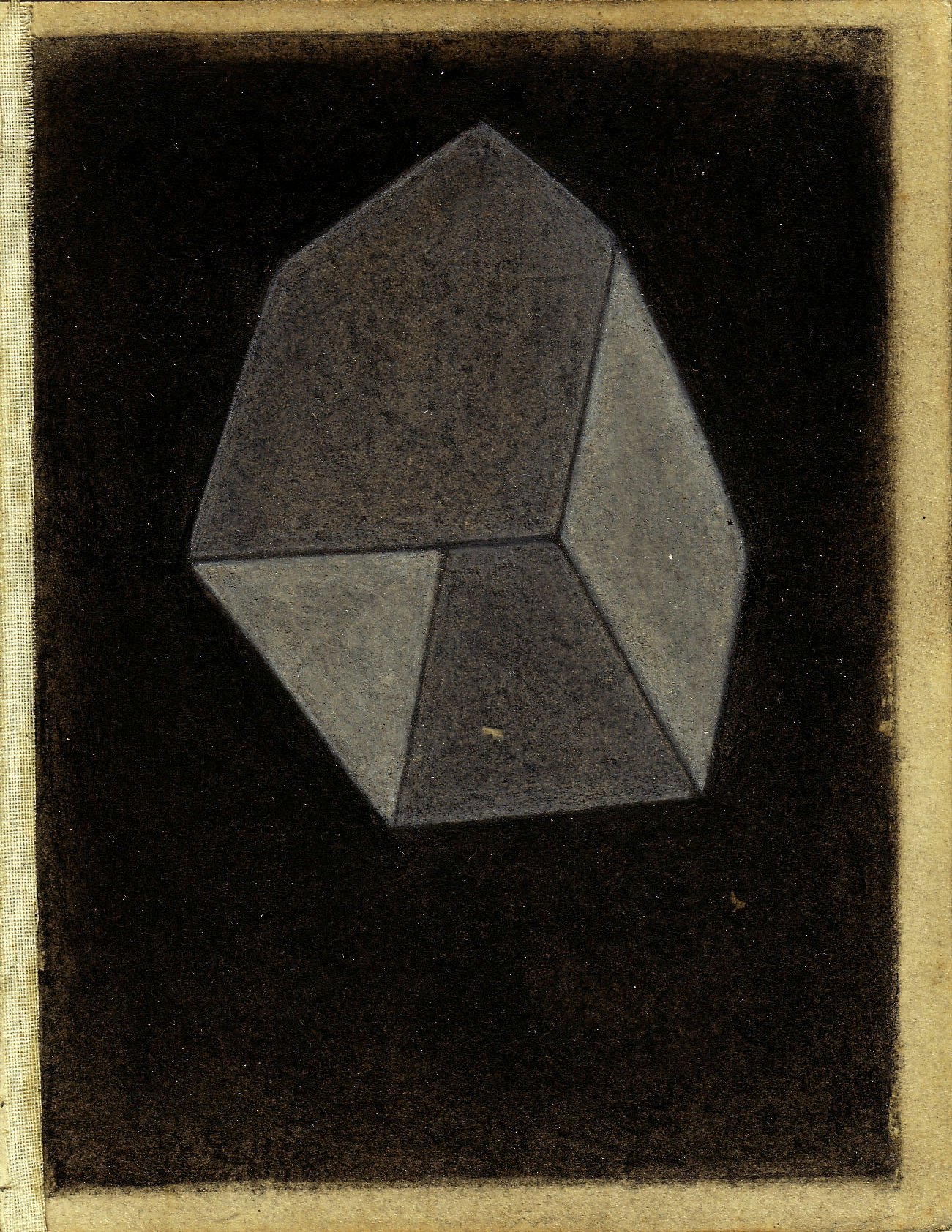

The house ? It is a triangle and a rectangle. It is a closed, rigid, and compact form, without openings, opaque due to layers of amalgamated charcoal. It does not reference habitability, nor does it evoke living spaces—only a visible element upon which the spectator’s gaze will settle.

The form makes us say “house”, and yet everything distances us from it—from opacity to compactness without openings, neutralized by repetition. In the end, the house becomes the foundational module of a spatial language, the first repeated word of a syntax whose phrases invent, with each new exhibition, a different story.

Black is both charcoal and line, shadow and impenetrable volume. It is not merely a color but a substance shaped by slow labor: to amalgamate, to sand, to glue again, to approach the degree of matteness and the anonymous sameness of form, where all reference is abolished. The patience of black, sought after.

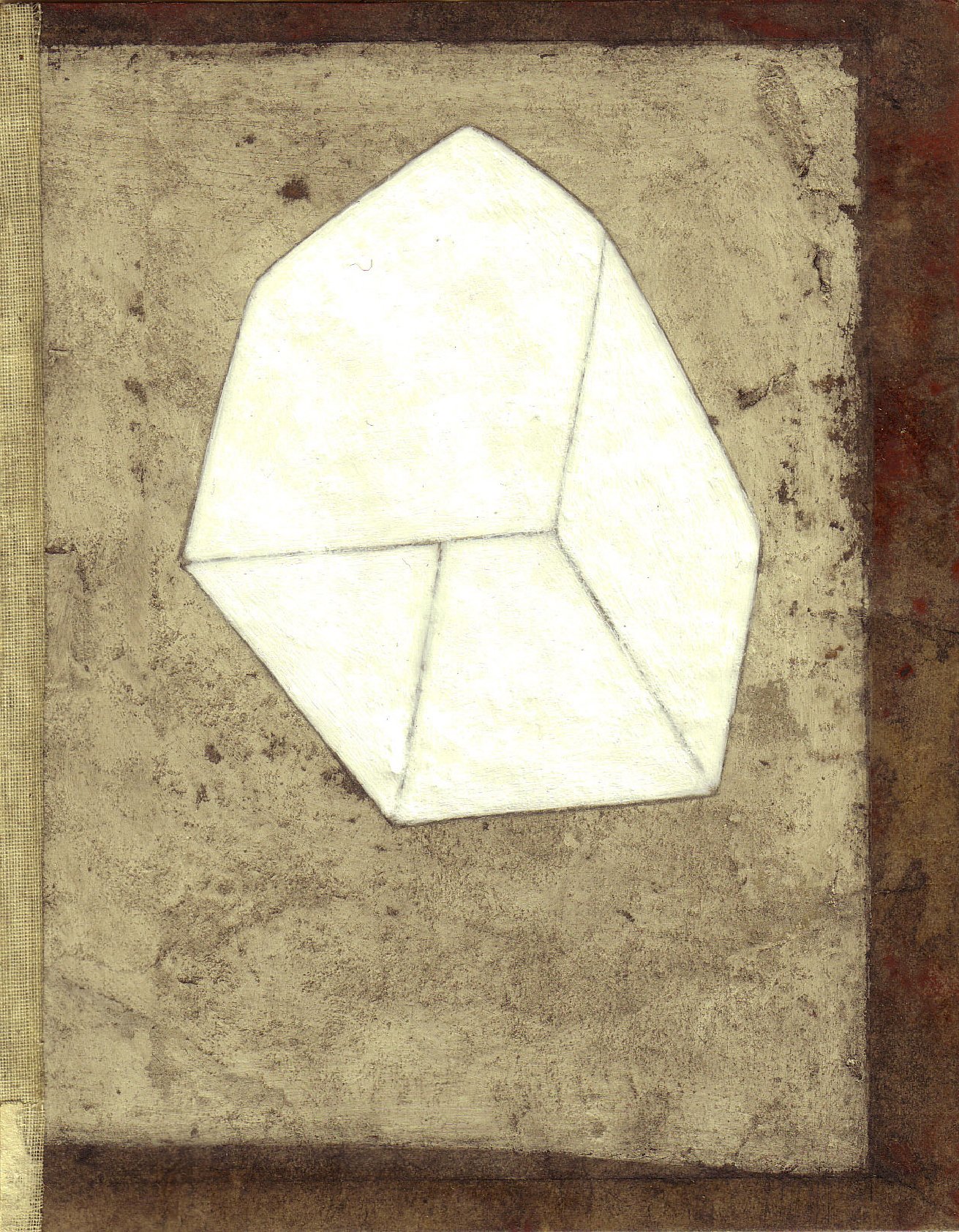

In contrast, the rare white of zinc surprises. By its scarcity, it intensifies its presence and recalls that light—the light of bulbs and neon—is treated as material throughout Alain Quesnel’s work.

« Intensity is silent

Its image is not

I love that which dazzles me, then deepens the darkness within me. »

René Char, « Redness of Early Risers », « The Early Risers », 1950

Make no mistake : the drawing does not lock itself into a mechanical opposition between the diffraction of white and the contraction of black. The artist plays freely with the combinations allowed by the encounter of these two colors. The chemistry of poppy oil, paint, graphite, and paper does the rest.

The materials favored in his installations—humble or ordinary, accessible and common, such as charcoal, zinc, copper, metal—bring us back to elemental experiences: roughness and smoothness, warmth and cold… But beyond that, through the concrete use of energy—electricity and its conduction—and raw material—charcoal, extracted and transformed—he offers artifacts whose function is to put the viewer in a state of tension, to engage them in the proposal.

The austerity and asceticism of the forms, the spatial arrangements and dispositions, assert themselves. And yet, there is something here of a celebration of materials—copper, zinc, wax, charcoal—recognized in the extreme refinement of gesture, far from any aestheticization of elements removed from their context. If the pieces become triggers of experience or activate unknown sensations, it may be because everyone recognizes the wooden beam, the copper wires, the black charcoal, the sack, the bare bulb—and simultaneously perceives the gap, the displacement carved between their everyday use and function, materialized by singular objects. Forms that suggest… yet are not…

An ideality of which Malevich thought, translated by Jean-Christophe Bailly in « The Workshop of Infinity, 30,000 Years of Painting » (2007) : « That energy, and the desire through it to touch a space less narrow than that of the old story of man, set within the horizon of a world of things. »

Everything unfolds in imperceptible gaps—one recognizes a form, a simple and identifiable volume, an idea. Simplicity in appearance, or *A bruit secret*, presented by Marcel Duchamp in 1916 : « A ball of twine between two copper plates, held together by four long bolts. Inside the ball of twine, Walter Arensberg secretly added a small object that produces a sound when shaken. To this day, I do not know what it is, nor does anyone else.

On the copper plates, I inscribed three short sentences, in which letters were missing here and there—like a neon sign where a letter is not lit, rendering the word unintelligible. »

Anne Champigny

Exposition A l’envers de l’endroit – Château de Tours – 2010